By Marco Silva, @BBCMarcoSilva, Climate disinformation reporter

On X, formerly Twitter, he regularly posts videos of himself weeding his land, planting garlic, or picking avocados – offering viewers a window into life in rural Kisii, south-west Kenya. While farming content may get him clicks, likes, and retweets, it is Mr Machogu’s denial of man-made climate change that has helped supercharge his online profile.

Since he began posting debunked theories about climate change, he has received thousands of dollars in donations – some of which came from individuals in Western countries linked to fossil-fuel interests. Mr Machogu insists this has not influenced his views, saying they are genuinely held.

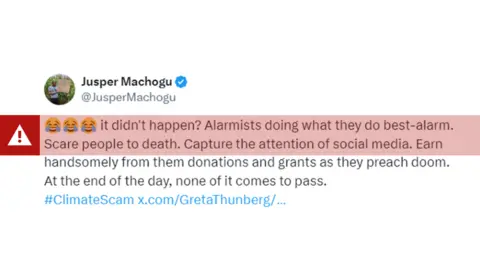

Scientists have proven that the Earth is heating up because of greenhouse gases that are emitted into the atmosphere when we burn fossil fuels – like oil, gas, or coal. But Mr Machogu disagrees. “Climate change is mostly natural. A warmer climate is good for life,” Mr Machogu wrongly claimed in a tweet posted in February, along with the hashtag #ClimateScam (which he has used hundreds of times).

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says Africa is “one of the lowest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions causing climate change”. However, it is also “one of the most vulnerable continents” to climate change and its effects – including more intense and frequent heatwaves, prolonged droughts, and devastating floods.

Despite all this, Mr Machogu continues to insist “there is no climate crisis”. On social media, he has repeatedly posted unfounded claims that man-made climate change is not only a “scam” or a “hoax”, but also a ploy by Western nations to “keep Africa poor”.

“[His views] are definitely coming up from a place of lack of understanding,” says Joyce Kimutai, a climate scientist from Kenya who has contributed to IPCC reports.

“This is not religion, this is not just belief. It’s about analysing the data and seeing changes in the data. “Saying that climate [change] is a hoax is just really not true,” Dr Kimutai added. Mr Machogu began tweeting false and misleading claims about climate change in late 2021, after carrying out his “own research” into the topic.

Since then, he has launched his own campaign – which he dubbed “Fossil Fuels for Africa” – arguing that the continent should be tapping into its vast reserves of oil, gas, and coal. “We need fossil fuels to develop our Africa,” Mr Machogu tweeted last year.

This view appears to be shared by some African governments, who have given their go-ahead to new oil and gas projects despite pledging to “transition away” from fossil fuels. Leaders like Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni have argued that it is hypocritical for Western nations to impose restrictions on African states, when they have become rich from fossil fuels.

But climate activists like 24-year-old Nicholas Omonuk, from Uganda, point out that fossil fuel exploration has not always been a synonym for growth and development in Africa. “In [Nigeria’s] Niger Delta, there’s been oil extraction since the 1900s, but people there are still poor and are still suffering from health risks and from pollution,” he said.

Crude-oil-pollution-has-affected-fishing-and-farming-communities-in-Nigerias-Niger-Delta

But by tracking conversations involving Mr Machogu’s X handle, BBC Verify found that most users engaging with his account are actually based in the US, the UK, and Canada. Many of those users also promote conspiracy theories online – not just about climate change, but also about vaccines, Covid-19, or the war in Ukraine.

However niche its views may be, this online community has thrown its support behind Mr Machogu and helped him fund his campaign. “Through saying whatever I say, I have seen my follower count going up and I’ve got people reaching out to me saying: how can we help you?,” he said.

BBC Verify looked at fundraising pages set up by Mr Machogu and found that, in the last two years, he has raised more than $9,000 (£7,000) from donations. Mr Machogu has posted online about using some of these funds to furnish his new home.

But he also claims to have used donations to help dozens of local families by building a borehole for water, distributing gas bottles for cooking, or connecting their homes to the electricity grid.

Among his donors were individuals with links to the fossil fuel industry and to groups known for promoting climate change denial. But Mr Machogu rejects suggestions that those donations have had any impact on his opinions on climate change.

“Nobody has told me to change my views,” Mr Machogu insists. “I don’t have a problem with making money while saying what I believe I should say or doing what’s good for my community.”

Podcast: The Kenyan influencer championing climate denial

A US fossil fuel advocate paid for Mr Machogu to travel to South Africa for a conference promoting African oil and gas late last year. And, just months before, a film crew from the UK travelled to Kisii to interview him for a new documentary that described climate change as an “eccentric environmental scare”.

To some, Mr Machogu’s new-found popularity has not come as a surprise. “There’s been a real explosion in fossil fuel development projects in Africa,” says Amy Westervelt, a US investigative climate reporter who covers attempts to obstruct climate policy.

“And because a lot of countries are passing policies that are limiting fossil fuels, Africa is also seen as a big market. “So, it’s very helpful to have people in Africa saying: ‘We want these projects’.” That is certainly a point Mr Machogu has made – again and again – on social media.

But Dr Kimutai says his promotion of fossil fuels, along with his denial of man-made climate change, could have consequences. “Because we still have low climate literacy levels in Africa and in Kenya, and if that conspiracy theory spreads to communities or to people, it could just really undermine climate action.